Prof. Moreno: It’s good to have a LEZ but it’s even better to be a LEE

Cities should not merely “have” low emission zones (LEZ) but should themselves “be” comprehensive Low Emission Environments (LEE) – states prof. Carlos Moreno, cities expert and author of the famous concept of the 15-minute city, in an exclusive interview with the LEZ Laboratory website. He emphasizes that a future, sustainable, and user-friendly city is one where the majority navigate through dense urban spaces primarily by walking, cycling, and utilizing public transport.

As for today, in the current state of affairs, should every city have a Low Emission Zone?

Embracing the 15-minute city philosophy, a pivotal challenge ahead is to sharply curtail the environmental and climate impacts of urban spaces. A crucial first step towards more sustainable urbanity involves reducing greenhouse gases, predominantly emanating from vehicles. While the implementation of low-emission zones is indeed a praiseworthy advancement, I assert that cities should not merely “have” these zones but should themselves “be” comprehensive low-emission environments. Time is of the essence, demanding a systemic reshaping of our urban landscapes to facilitate a carbon-neutral mobility network. My envisioning of a future, sustainable, and user-friendly city is one where the majority navigate through dense urban spaces primarily by walking, cycling, and utilizing public transport.

Does a 15-minute city need a Low Emission Zone?

The 15-minute city is not a traffic management strategy but a lifestyle that enhances quality of life, enabling individuals to spend more meaningful time near their homes amidst a wealth of services in a polycentric urban environment. The goal is not to battle against cars per se, but to resist car dependency, which encompasses habitual vehicle use, even for brief trips in residential areas. In the “15-minute city”, residents can reach six essential social functions – living, working, accessing healthcare, shopping, learning, and personal development – within a 15-minute walk or cycle from their dwellings. Urban developments fostering mobility are crucial to encouraging soft mobility in daily life: safe, wide cycle paths, and lush, friendly pedestrian areas. Cars are demoted: parking is minimized and commodified, with select streets becoming car-free. Public spaces are liberated from vehicles and returned to pedestrians. In the 15-minute city, elongated, carbon-intensive travels are outliers. This urban model inherently diminishes carbon emissions through its operational design, negating the necessity for specified low-emission zones: the 15-minute city is, in essence, a low-emission city.

Is the 15-minute city a concept – in a way – of a concentration of micro-cities?

No, the 15-minute city is a polycentric city, but it remains one city. Its neighborhoods remain complementary, interdependent and interconnected. Its rules and operations remain those of a “single” city. The management of the city and its services must remain centralized, large-scale facilities cannot be created everywhere… The 15-minute city should not be understood as a multiplication of small towns, but as an improvement in the fluidity and quality of life of a city.

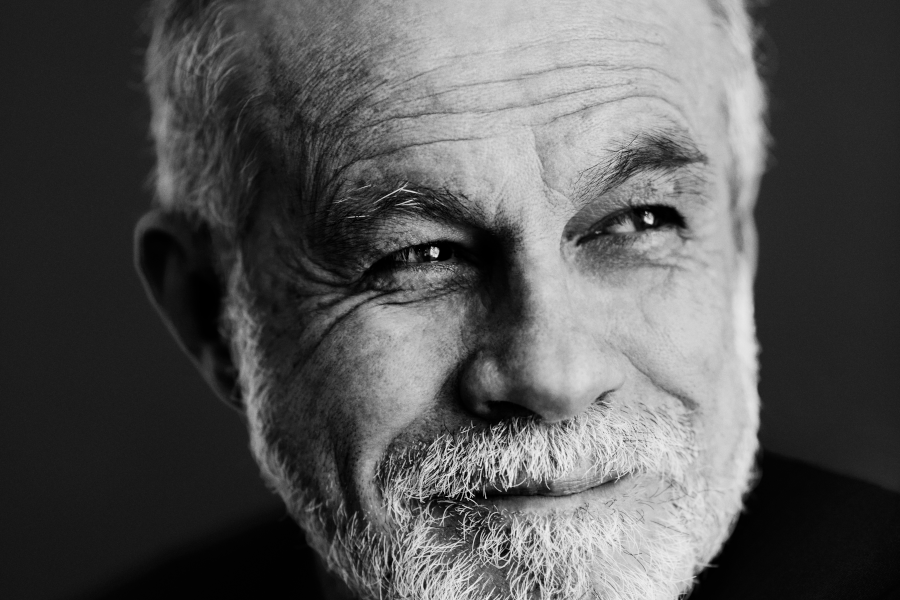

(photo: Thomas Baltes)

Does nature and its solutions, such as beehives, inspire you in your work?

Urban biomimicry is interesting because, as the French saying goes, “Mother Nature has a way of doing things”! We can find forms or processes in nature that can be reproduced to develop appropriate and sober urban, architectural and health features… My work is mainly inspired by the ecosystemic characteristics of nature, of the planet, of species. I consider the city as a whole, as an ecosystem, with its mobile and immobile, built and unbuilt, organic and inorganic, real and virtual components. This means taking an interest in the relationships and interactions of influence, dependence and mutual benefit between species. Rather than taking inspiration from and copying nature, I’m in favor of massively integrating nature into urban spaces to refresh our cities and make them more pleasant. What better than nature to create the benefits of nature?

What do you think is a better, or even the best, alternative to private cars – from the point of view of today’s car users?

Undeniably, any low-carbon transport option surpasses private cars! With respect to both operational greenhouse gas emissions and production life-cycle analysis, private cars persistently emerge as a concern. There is no universal solution: each user must identify the alternative that optimally aligns with their individual needs, contingent upon their urban context and daily necessities. Our approach isn’t about enforcing punitive obligations; rather, we aim to persuade individuals that a lifestyle change is imperative. Climate change is a persistent reality, and it is solely through our behavioral modifications that we can adapt and mitigate the already evident challenging impacts.

Prof. Carlos Moreno is a cities expert and creator of the concept of the 15-minute city. For this contribution, in 2022 he received the UN HABITAT “Scroll of Honour”, one of the most prestigious awards given to those who work for sustainable urbanism. He was also awarded the Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French Republic (2010) and the Prospective Medal from the French Academy of Architecture (2019). Prof. Moreno’s website: https://www.moreno-web.net/.

(illustration photo: ETI Lab, IAE Paris – Paris Sorbonne Business School)