This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Developing a LEZ – lessons from the UK and Warsaw

Introducing a Low Emission Zone (LEZ) is both technically complex and politically challenging, and so building a robust evidence base to support the case for a LEZ is crucial to its success. In this case study we set out some of the key lessons we have learnt from building this evidence for a number of cities in the UK such as Bradford and Southampton, as well as working with the City of Warsaw on their LEZ scheme.

The UK has a number of cities with a LEZ (or as we call them Clean Air Zones) in operation. These cities were required to assess and implement a LEZ to tackle breaches of the air quality limit value for NO2. The schemes are based on road user charging legislation, which means that vehicles not meeting the LEZ are charged to enter, and the emission standards for the LEZs were set nationally. The zones can also be enforced by Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) technology linked to the national vehicle registration database. In summary, there are some differences with the situation in Poland, however the overall process of developing and justifying a LEZ scheme will be similar.

The development process

The process for designing a LEZ is not necessarily a linear one and will generally have more than one iteration as different scheme options are considered. Assessing these options will provide the evidence needed to define the most effective scheme for your city. The two key pieces of evidence to support a scheme are generally:

- An impact assessment of the scheme options – in terms of effect on traffic and air pollution

- The economic case for the scheme – what are the costs and benefits, and who is affected and how?

When developing options, it is useful to first come up with a long list, based on your understanding of the problem including where are the pollution hotspots, what vehicle types are causing this and what might be politically acceptable. Then an initial sifting of this list using a qualitative assessment, for example in the form of a multi-criteria analysis (MCA) assessment, can help you focus in on the most likely options that you then want to assess further.

Impact assessment

This assessment focuses on the air pollution impact of the scheme, as this is the primary goal of LEZ implementation. The key steps to this assessment are:

- Assessing the impact of the LEZ on the traffic flows and vehicle fleet composition.

- Determining how this will then affect transport emissions.

- Translating this to the actual impact on pollutant concentrations.

The first step is arguably the most difficult in trying to get an understanding of how many people would upgrade their vehicles or change their travel patterns in response to the scheme. Approaches to this can include evidence from the implementation of similar schemes in other cities, specific behavioural response surveys or the use transport models to assess the travel behaviour response to a LEZ. In the UK, transport models were the main source of this data, complemented by some surveys. However, for our work in Warsaw, the transport model owned by the city was not designed to provide this kind of assessment. Therefore in this case we applied a combination of information on responses to schemes in the UK, some local survey work, a focus group with local businesses, and the city’s transport model.

Translating the anticipated behavioural response into emission changes across the road network is the next key step. Key to this is detailed traffic and fleet composition data and traffic models are again an ideal source which we applied in both our work in the UK and Warsaw. This is then combined with vehicle emission factors which are typically European COPERT data. However, more recently with some of our UK work and in Warsaw we have been adjusting these factors using ‘real world’ emission measurements from remote sensing equipment. These provide a detailed understanding of the local vehicle fleet and what its emissions performance is, that would not otherwise be captured.

Measuring real world vehicle emissions (photo: Ricardo)

The modelled changes in emissions are then fed into an air dispersion model and subsequently combined with information on non- road transport emissions, which are often referred to as background sources. Getting information on these other sources can be difficult. In the UK, we have national level data available at a 1 km resolution across the country both in terms of emissions and concentrations. Again, this was not available for our work in Warsaw and we therefore worked with a combination of low resolution satellite data and air quality monitoring data to provide background pollutant concentrations to complement our modelled concentrations from transport.

With any modelling assessment there will always be uncertainly and the behavioural response assumptions are typically the main one. Trying to assess this uncertainty and what it might mean for the results is another important aspect of impact assessment. This is generally done using sensitivity analysis where we adjust some of our assumptions and see what impact this has. For example, if we increase our assumption on how many vehicles divert around the LEZ, what impacts would this have and would it reduce the effectiveness of the scheme significantly?

In summary, for Warsaw we provided a model which pulled on a range of key sources of information including the city’s transport model, satellite data for background pollution and remote sensing vehicle emission data to get real world performance of the local vehicles. Information on behavioural response built on experience from London’s ULEZ and was complemented with sensitivity analysis.

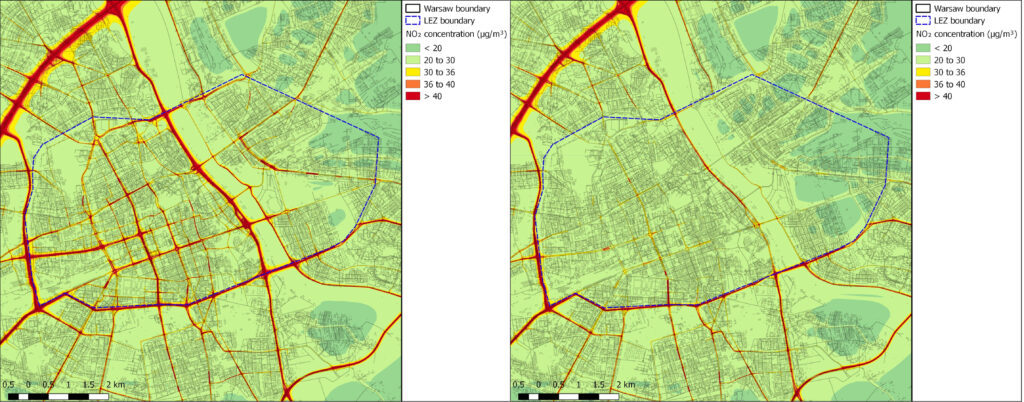

Air Pollution model results for Warsaw without and with a central LEZ option (source: Ricardo)

Building the economic case

A Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) provides the core of the business case for the LEZ and aims to value all impacts of the scheme in financial terms so that they can be compared to assess whether the benefits outweigh the costs. We have developed our own LEZ specific CBA model that we have used in both the UK and Warsaw, with the key components covering:

- Health impacts – the monetised mortality and morbidity impacts from a change in pollutant concentrations;

- Capital cost of vehicle upgrades to comply with the LEZ;

- Changes in fuel and non-fuel vehicle operating costs, and change in GHG emissions, associated with vehicle upgrades;

- ‘Welfare’ impacts of trips cancelled due to the LEZ (i.e. the lost value to the individual of the activity foregone/not undertaken);

- Change in travel time from diverted trips due to the LEZ;

- Implementation costs.

The health impact assessment uses the outputs of the air pollution modelling combined with standard methodologies from the EC and EEA on health impact monetisation. The estimation of vehicle upgrade costs and operating costs requires information on the vehicle fleet from localised ANPR data (as used in the air pollution modelling) and vehicle registration data to understand the number and type of vehicles that need to be upgraded. This is then combined with local or national cost information on vehicles (both new and second hand) and fuel costs. For the UK we had detailed cost data built up over a number of years. For Warsaw we adjusted this data with more generic cost data that we were able to source for Poland. Welfare and travel time costs require use of outputs from the city’s transport model and the scheme implementation costs are typically provided by the city authority and focused mainly on the costs of the enforcement approach being used.

CBA however only looks at things in aggregated form which can potentially hide inequity in how those cost and benefits are distributed. For example, do some sectors of society bear higher costs or get greater benefits from the LEZ than others? This analysis is known as distribution analysis. The distribution of air quality benefits can be assessed by overlaying the change in pollutant concentrations with demographic data to see who may receive the greatest benefit. Similarly, in terms of upgrade costs it would explore vehicle ownership data to understand who owns vehicles affected by the scheme and the costs they may incur.

Distributional analysis can be very important in managing the political challenges of implementing a LEZ as it helps politicians understand who is affected. It can also be used to develop complementary measures to support those who may be most affected. For example, small businesses may struggle with the costs of upgrading vehicles and so a grant scheme targeting them could help the scheme be more politically acceptable. The same data used to assess upgrade costs in the CBA model can be used to estimate what level of support may be needed by residents or business to help them upgrade their vehicles. Another incentive that has been explore is the use of scrappage schemes and mobility credits to encourage drivers to relinquish an older vehicle in exchange for credits (based on the residual value of the vehicles) for use with public transport or car sharing services.

An good example of building a strong economic case is the work we carried out for the LEZ in Bradford, UK. The distributional analysis identified small local freight businesses as a key sector impacted by the scheme. Exploring this further, we assessed the costs needed to allow them to upgrade their vehicles to comply with the LEZ and helped develop a grant scheme to support them. Overall, the business case for the LEZ in Bradford was successful at securing £43 million in funding from central government for the main scheme and supporting measures.

Promotion graphic for the Bradford LEZ scheme and accompanying support measures for local businesses

Communicating for success

Consulting and communicating on your LEZ scheme is the final element in making your LEZ a success. Again, the evidence you have is important for effective communication and engagement, as it allows you to:

- Clearly show what the problem is and so why a LEZ is needed

- Explain the options you have considered and why you have chosen the preferred scheme

- Describe what the benefits and cost are likely to be

- Set out who could be impacted and how you are considering mitigating this

Having clear evidence on these points will help bring key stakeholders along with you and encourage support rather than opposition for your scheme. People want to know what it will mean for them and how you have considered them, whether they are businesses or residents.

Political will is probably the key determinant for taking forward a LEZ but having a robust evidence base is a close second. The evidence base can also help support and build the required political will in the first instance.

(photo: the author’s archive)

Dr Guy Hitchcock, Technical Director for Low Emission Cities, Ricardo

(illustration photo: Ricardo)